Top-10 Fictional Languages That You Can Learn

Here’s an interesting piece of linguistic history you may not be aware of: The entire language of Korean was actually a manufactured language, intended to be a simplified version of the comparatively more complicated Chinese.

Human history is surprisingly rife with manufactured languages. Most languages evolve organically, but occasionally some expert upstart will study linguistic trends, delve into the mysteries of historic syntax, and they’ll try to create something more efficient. Such experiments rarely work (Korean notwithstanding), being, as they are, a bit too obtuse for the casual speaker to want to learn; for instance there is an uninflected version of Latin in the world called Latin sine Flexione, created in 1903 for the purposes of mainstreaming Catholic masses. The most popular manufactured language is probably Esperanto, created in 1887, and it’s more popular offshoot Ido, which was the language that one William Shatner film was shot in. And don’t get me started on E-Prime. Or Ebonics for that matter.

The best manufactured languages, though, are the ones we geeks are lucky enough to come across in our geek fiction. What better way to make an alien race seem a touch more real, than create a native tongue for them? Their language can carry so much about their culture, their attitudes, and their evolution. If an author is clever enough, they can create an entire syntax and culture in their heads.

As there are literally hundreds of imaginary languages spoken throughout film, TV, literature, and pop culture in general, I will narrow down this list to the top-10 languages that, should you have the gumption and the interest, you can actually learn to speak. They may have supplementary language books, or they may just require multiple viewings of a single film, but they are all speakable languages.

Here then, are the top-10 imaginary languages you can speak.

10) Furbish

In 1998, The Furby was the must-have toy of the Christmas season. They were armless, furry, owl-like monsters, about six inches tall, that could mutter and mumble and eventually learn to speak with you. If you had two Furbies, they could be placed across from one another, and they could spend hours conversing with one another.

But there was more appeal to the toys than mere cutesy cooing; evidently, the more you interacted with your Furby, and the more time you spent speaking English to it, it would actually begin to imitate your English phrasing, and more and more English phrases would creep into its conversation. I don’t exactly know how this technology worked, but it did indeed seem to simulate language lessons.

If you paid careful enough attention to your Furby’s mumbling, though, you would begin to intuit certain phrases, and eventually come to understand what the Furby was saying. In essence, the creature had a language all its own, and you, mere innocent, toy-loving child that you were, were actually engaging in a complex linguistic exercise. The Furbish vocabulary isn’t that extensive, and the syntax is very simple, but, for many kids, Furbish was the first foreign language that they bothered to study.

9) Mondoshawan

It is the divine language.

Often, when a film director wants to have an exotic alien species in his sci-fi film, he will work with the actors to create the language together. This may make for some faulty linguistic structure, but a more natural reading. There are plenty of low-budget sci-fi films to feature actors mumbling random gibberish to themselves; even Lucille Ball did it in an episode of “I Love Lucy.”

One of the more impressive actor/director-created languages is probably the one Milla Jovovich and Luc Besson created for the 1997 sci-fi film “The Fifth Element.” Jovovich played a genetically perfect alien named Leeloo, who could kick massive amounts of butt, fall great distances without dying, and outsmart the greatest evil in the galaxy. Leeloo seemed to yammer in gibberish, but the trained ear might be able to catch a word here and there, and find that she is indeed speaking a real language.

Like Furbish, the given vocabulary of Mondoshawan was limited (between 300-400 words, depending on your internet source), but it was a real language with a real structure. Indeed, Jovovich and Besson would write letters to one another in Mondoshawan to practice. Jovovich got to make up the accent.

Sadly, there are no books on Mondoshawan in the world, but careful viewings of “The Fifth Element” might teach you a thing or two about how to speak divinely.

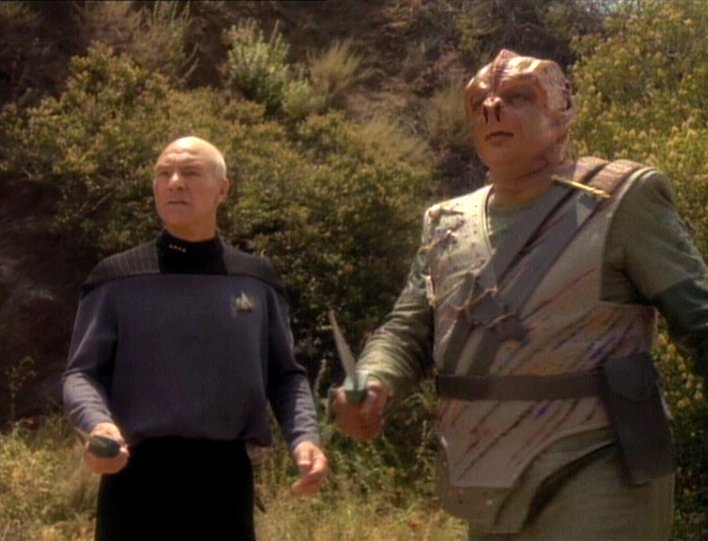

8) Tamarian

This language only appeared in one episode of “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” but the episode – entitled “Darmok” – was so well-written that many people remember not only the story, but the details of this oddball language.

The Tamarians, it seems, have a language that is indeed translatable into English, but it is so heavy reliant on mythology, metaphor and cultural imagery, that it sounds like babbling to the casual listener. The captain of the Tamarian ship greets Capt. Picard with the phrase “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.”Picard responds in a casual conversational tone. The people cannot understand one another.

By the end of the episode, you begin to see what the phrases mean, and how to communicate with a Tamarian. This is not only an ingenious conceit for a sci-fi TV show, but also casts an intellectual light on how your own language might be built, and how often we rely on cultural indicators to communicate, rather than bare words. Many site “Darmok” as one of the best episodes of this series, and, when you find yourself translating Tamarian in your head, you’ll understand why.

Watch the scene of Picard telling the tale of Gilgamesh to his companion. It’s a wondrous scene.

7) Simlish

What started as a cute joke in the video game “The Sims” soon blossomed into a full-blown linguistic exercise. Your digital human avatars – whom you had to feed, clothe, support, and help live – would, in conversation, mumble to one another like Furbies, creating a facsimile of speech without having to actually converse. Some obsessive began mumbling similarly to one another, and by the time “The Sims 2” came out, Simlish was already in wide usage amongst a certain, particularly frightening segment of the video game playing populace.

What could easily be mistaken for gibberish is actually a well-thought-out, if not particularly complicated, language. It’s essentially structured like English, with an ersatz vocabulary put in its place. Learn the vocabulary (which is based on several existing languages), and you have Simlish down pat. It was originally intened to be untranslatable, but fans being fans, the language grew on its own.

Indeed, thanks to one William Bibbiani, I have seen the above music video of Katy Perry’s “Hot N Cold,” sung entirely in Simlish. Welcome to a nerdier back corner of pop culture.

6) Na’Vi

James Cameron’s ultra-successful sci-fi film “Avatar,” while often criticized for its oversimplified story and comparatively shallow characterization, was, it has to be admitted, one of the most ambitious sci-fi films of recent memory. Cameron did not want to merely design a planet for a movie; his ambition was to create a real society of blue alien monsters called the Na’Vi. He created a life philosophy, some creepy Gaia-like psychic stuff (which didn’t read so well), and, designed an entire menagerie of alien creatures to live in his lush jungle on the faraway planet of Pandora. Whatever your problems with “Avatar’s” story, it does look amazing.

The most palpable element of the Na’Vi culture, though, was the language they spoke. Cameron, not content with magical devices like Universal Translators, had his aliens speak in their own tongue. He consulted with a linguist named Paul Frommer, and together they created a huge syntax and vocabulary. In interviews, Cameron claimed his ambition was “to out-Klingon Klingon.”

Given the film’s popularity, it should be no surprise that a small subculture of Na’Vi enthusiasts have emerged, and have shared their linguistic knowledge at the website listed here: http://www.learnnavi.org/. There are also books and other resources to help you learn. To my ear, Na’vi sounds like a romance language.

5) The Voynich Manuscript / The Codex Seraphinianus

The Voynich Manuscript is thought to have been written in about the 16th century, thanks to the carbon dating of the paper. It appears to be an encyclopedia of pharmacology, having chemical symbols and medical botany mixed in with (what appears to be) instructions. The origin of the text is unknown. The text seems to be written in some sort of code, or is, perhaps some sort of language in itself. The manuscript is named after Wilfrid M. Voynich, who unearthed the text in 1912, although the text’s author(s) remain/s a mystery.

If you are a clever linguist, and have an eye for cryptography, then you have probably already heard of the notorious manuscript, and it’s possible that you have already taken a crack at it. The alluring, misty history of The Voynich Manuscript makes it an irresistible project for nascent obsessors, attracting all lovers of linguistic mystery into a potentially unsolvable enigma, threatening to consume you, and always offering the promise of an answer just around the corner. It is available in print form for the curious and the brave.

The Codex Seraphinianus has much clearer origins, but is just as mysterious a text in many ways. Authored by the mad surrealist Luigi Seraphini in 1976, The Codex can be seen as an epic, mysterious art project. It is, at first glance, an encyclopedia of sorts, cataloguing the flora and fauna in a bizarre parallel universe where chairs grow from trees, houses and hippos are the same thing, and planets provide canoes and telephones for the oddly-dressed human-like beings that live nearby; The Codex may be a dissection of taxonomy. As you thumb through, though, you begin to experience a strange meditative feeling, and begin to suspect that there is more going on here than a mere catalogue…

The book is made all the more opaque by the as-yet untranslated script that Seraphini invented. He has remained notoriously opaque about the meaning of The Codex, and has not given any clues as to the structure of the imaginary language within. Is it a cipher? Is it a new language? Like The Voynich Manuscript before it, The Codex has repelled all attempts at deciphering it.

These languages are available for study. If you learn to speak either of them, be sure to tell someone, as you have solves two of the greatest language oddities in literary history.

4) The Demonic Language

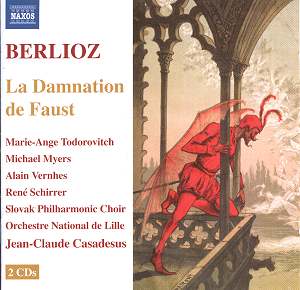

I understand that the pages of Geekscape have few references to grand opera, so I implore patience for this one.

In 1849, Hector Berlioz, influence by the famed book/play by Goethe, wrote an opera of the famous Faust story called “The Damnation of Faust.” It was a huge hit, and, to this day, is one of the more hummed operas. Its form is notoriously defiant of definition, and Berlioz himself insisted that it was not an opera, per se, but more of a légende dramatique.

Berlioz felt that the human characters, as well as Mephistopheles, would be allowed to sing in their native French, but when faced with the demons of Hell, French would no longer do. He tried to compose in several other language at first, trying to attain the true wicked evil of demons just right. Russian and German would not do either. It was Berlioz’ only recourse to compose his own language.

The result is, well, musical. People forget that language is more than just a series of letters and syntactical rules. It is a cadence, a song, a music unto itself. Berlioz did not just compose a boring series of rules, he wrote linguistics from the heart. The Demonic Language of “The Damnation of Faust” is wicked, evil, horrifying. It is a guttural utterance from the bowels of Hell. And it is beautiful.

3) Ulam

The 1981 film “Quest for Fire,” based on a 1911 novel, is a typical adventure story about cavemen (c. 80,000 years ago) wandering the countryside, looking for fire, but is especially marked for its verisimilitude and, notoriously, its own caveman languages. The central tribe of Neanderthals that our narrative follows, is a tribe of Ulam, who speak a rudimentary language, constructed for the film by famed author Anthony Burgess.

This is a language that not only follows its own rules, and can be learned over the course of the film, but one that seems to presage the languages that were to come after it. Even more cleverly, the film’s director, Jean-Jacques Annaud, had other tribes speak other languages. When the homo sapiens first appear, for instance, they speak an advanced Cree language.

Add to this a language of gesture and sign (created by Desmond Morris, a primate expert), and you have one of the most fully-realized, historically accurate imaginary languages in cinematic history.

2) Quenya, Telerin, and Tengwar (The Elvish tongues)

J.R.R. Tolkien, that geek deity, was, famously, a linguist before he became the author of some of the most celebrated fantasy novels of all time. He was one of those upstarts who, having studied language intently, felt he could create his own, better tongue for humanity to follow. He never tried to pass off his own real-life language, but, thanks to the creative pseudo-cultural-study-cum-great-big-adventure novels The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien was given free rein to create what he wanted.

Tolkien imagined several different races of being, each with their own culture, each culture with their own factions, and each faction with their own languages. Most notable of the cultures he created was probably the culture of the Elves, who were a tall-standing noble race of cerebral aesthetes, and snotty bluebloods. The Elves had several tribes, each of which spoke their own language, and each of which had a history as to how they came to be, and how their languages evolved over time. There were sets and subsets of each Elvish tongue.

Many assume the Elves’ language to be based on Gaelic, or some other ancient language of the Isles, but, some cursory internet research reveals that the Elves’ language was based very closely on Finnish, a tongue that Tolkien had a particular fondness of.

There are volumes written on the Elves’ languages, and it can be learned through careful study.

1) Klingon

I’m sorry to be so obvious with my number one pick, and I’m sorry to include two languages from “star Trek” on the list, but Mark Okrand’s introduction of Klingon into the pop culture canon is probably one of the most momentous events in geek history. Originally conceived to fill a scene or two in “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” in 1979, it was eventually developed into a full-fledged languages that has resulted in Klingon language camps, Klingon filking, and Klingon translations of Shakespeare.

This is not a language of mere replacement vocabulary, nor is it necessarily influenced by existing Earth languages. Klingon (or tlhIngan Hol) is a beast unto itself. It has its own grammar. It has its own inflections and pronunciations. This is not a hobbyist coming up with something fun for a single film. Okrand managed to introduce an entire new langue into the world. And he did it for “Star Trek.” How cool is that? Klingon has taken on a life of its own, and exists even outside of the TV shows and movies.

There are several books of grammar and vocabulary available in bookshops, and I, nerd that I am, even have the Klingon language tapes that were once readily available to the aspiring Trekkie. What’s more, there is a Klingon Language Institute (http://www.kli.org/) to help promote its usage.

This pop culture juggernaut may be used as the punchline for numerous geek jokes (both for, and at geeks) but it cannot be denied that it is the most ubiquitous fictional language in the world.

Witney Seibold is a hardworking writing living in Los Angeles with his lovely wife and his love off the off-kilter. He works at a movie theater, and sees more movies than you do. He writes film reviews as well, having published over 700 articles to date on his own ‘blog, Three Cheers for Darkened Years! which can be accessed at the following address: http://witneyman.wordpress.com/ Leave some comments, eh?