Homo Superior, Or Just Plain Homo?

In light of the impending release of X-Men Origins: Wolverine (to theaters anyway. Snap!) now is as good a time as any to reflect upon comicdom’s biggest and most beloved gay allegory, The X-Men. While Marvel’s mutant population has always been a metaphor for race relations as well, I’m gonna go out on a limb here and say that it is the gay underpinnings that have proven to be stronger, at least in the modern era. The similarities between real life gays and lesbians and the fantasy mutants of the Marvel Universe are, well…uncanny (sorry guys, I couldn’t resist) Born looking and sounding like everyone else, their true nature emerges around adolescence, making them a target for the world at large. Seeking to find others like them, they either adapt and become contributing members of society at large, or they become angry and bitter and don’t trust “normal” people due to not being able to get past the way they were treated as youngsters. And many choose to remain hidden, hoping no one figures out who they really are, sometimes for their entire lives. With this description I could be talking about the X-Men, or I could just as easily be talking about any gay person you might know.

The Early Years

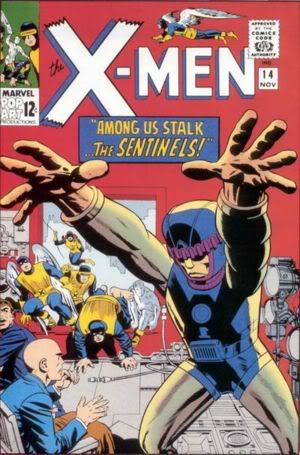

Okay, in fairness, the X-Men were not always such a big gay allegory, as that would have been way too much for the time in which they were created. If anything, the underpinnings for the book were rooted more in the black civil rights movement. But even those racial undertones were pretty much non explicit back then. It was all just a bit too much for a comic aimed at kids and teens in the early 60’s. In that first issue of X-Men in 1963, there were little hints of the notion of mutants as a separate race, with its own civil rights issues and prejudices to deal with. In Stan Lee’s own words, “the whole message of X-Men was love they fellow man. He may have wings growing out of his back, or beams shooting out of his eyes, or he may be a different color or a different race, but he’s still your brother. It’s wrong to hate or persecute people because they are different than you, or worship differently than you do” But let’s be honest; when Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created the concept back in 1963, what they really wanted was another team book to cash in on the huge success of their initial team effort, the Fantastic Four. Any civil rights metaphors were secondary to telling stories about kids with super powers fighting giant robots. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

With X-Men, Stan Lee wanted to create a team that looked like the Fantastic Four but were as hated by the general population and feared as Spider-Man was. But Kirby’s heart was never as into the angst and teen melodrama as Stan Lee was, so he left X-Men with issue #18 to focus on the more grand and cosmic adventures of the Fantastic Four and Thor. Without the Lee/Kirby combo, sales of X-men plummeted. And X-Men’s sales were never really that great to begin with. The book limped along till 1970 when it was finally cancelled. It would be five more years till Professor Xavier’s students would get another chance at success.

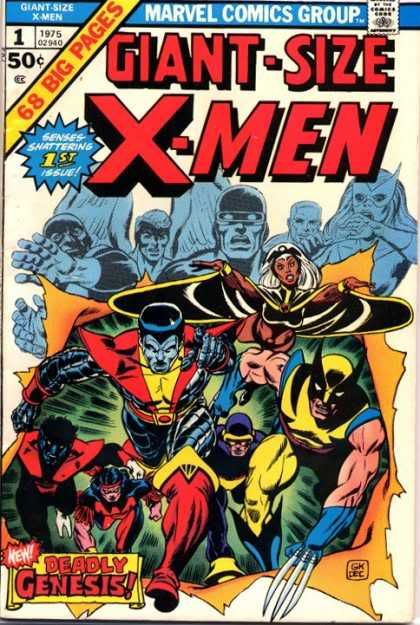

Second Genesis: X-Men Begins to Fulfill It’s Potential

In 1975, editor Len Wein decided they needed a book with a more international flair, since Marvel Comics were starting to be sold worldwide. It was decided that X-Men would be revived and would be that title. First thing they did was get rid of most of the lily white cast, with the exceptions of Xavier, Cyclops and later Jean Grey. Now, the book about allegorical minorities would actually have minorities in it. New writer Chris Claremont took all the implied metaphor of a persecuted minority from the early issues of the title and made it explicit. Charles Xavier was now a Martin Luther King type figure, who wanted nothing more than peaceful co-existence with man and mutant. Magneto, his opposite number, was transformed from a straight up villain into a sympathetic Malcolm X type figure, who wanted what was best for his people by any means necessary. In a world where the U.S. military creates Sentinel Robots to hunt down mutants, how bad a guy can Magneto really be?

By the early 80’s, X-Men under Chris Claremont’s guidance was Marvel’s best selling title. In 1982, Chris Claremont produced the first X-Men graphic novel, God Loves, Man Kills. Meant by Claremont to encapsulate everything the X-Men was about, the book was about an evangelical preacher named Reverend Stryker who stirs up religious anti mutant hysteria resulting in a mutant bashing of a young kid. The similarities between Reverend Stryker and the likes of Fred Phelps and his “God Hates Fags” rants were obvious and timely. Also introduced around this time were anti mutant rights characters like Senator Kelley, who would try to pass laws against mutant rights. The similarities to the then in it’s infancy gay rights movement were obvious, although I doubt they were to the vast majority of the young male readership.

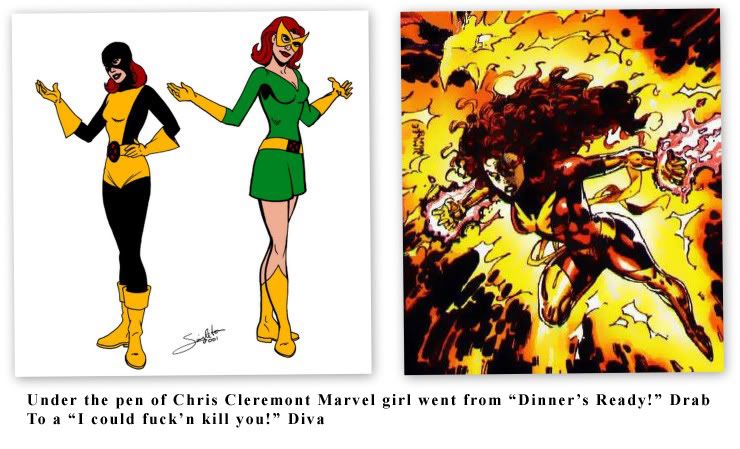

Chris Claremont introduced a lot of other elements that appealed to young gay readers like myself. The women in the 60’s Stan Lee comics were pretty much just relegated to being the girlfriend, or the member of the team with the weakest powers who was always being kidnapped and rescued by the boys. Such was the case with Marvel Girl, AKA Jean Grey. Chris Claremont took her and made her the uber powerful Phoenix, and made Storm probably the second most powerful member of the team. Just for the Diva Factor alone, X-Men appealed to me more than most comics. It should also be noted that the earliest and most prominent LGBT characters in mainstream comics (Northstar and Mystique) were introduced by Claremont in the pages of X-Men. After Claremont left the title, other queer metaphors were introduced to the book, such as a virus originating with mutants called the Legacy Virus, which eventually begins to infect normal humans and causing even more anti mutant hysteria. All of this was going on in the comics while the AIDS epidemic was at it’s worst.

The Mutants Go Hollywood. West Hollywood That Is.

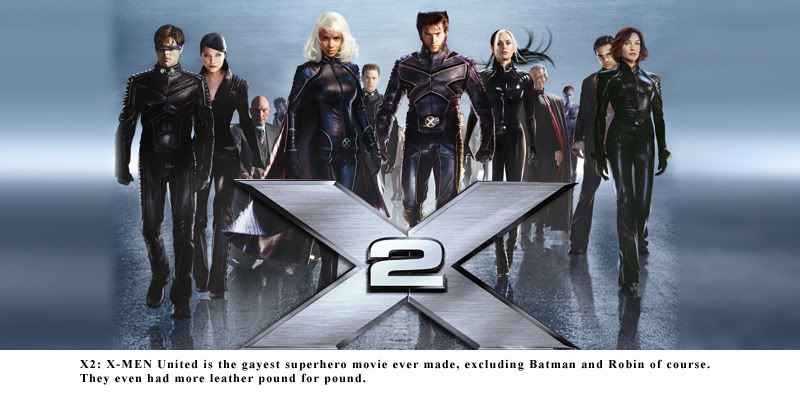

The GLBT underpinnings were felt most strongly in the first two X-Men films, made by openly gay director Bryan Singer and starring openly gay actor Ian Mckellen as Magneto. Drawing largely from God Loves, Man Kills, X2 even has a scene where young Ice Man “comes out” to his family as a mutant. And while that scene may be super on the nose, I always preffered the scene where Nightcrawler (played by yet another queer, Alan Cumming) asks shape shifter Mystique why she doesn’t just look normal and try to fit in all the time, instead of her usual blue and scaly self. “Because we shouldn’t have to” She says to him. She might have been a villain, but in that scene she was my hero. The third X-Men movie tries to tackle the notion of “reparative therapy” with it’s story of a mutant “cure”, but sadly director Brett Ratner wasn’t too interested in the metaphors of the X-Men and more in the explosions. Writer Joss Whedon did a far better job of dealing with a cure for mutancy with his early run on Astonishing X-Men comics.

The LGBT allegories continue in the X-verse, and I doubt they are going away any time soon. In the current comics, San Fransisco has become a mutant safe haven, much as it was (and continues to be) a safe haven for gay people in real life. The Ultimate X-Men version of Colossus is queer. And in the current issues of Uncanny X-men, the state of California is trying to pass “Proposition X,” a law banning mutants from having children. Sound familiar? A lot of these parallels are indeed a bit on the nose, but if it changes the mind of one young (or old) reader to open up their minds that being different isn’t a bad thing, then I’m more than OK with it.

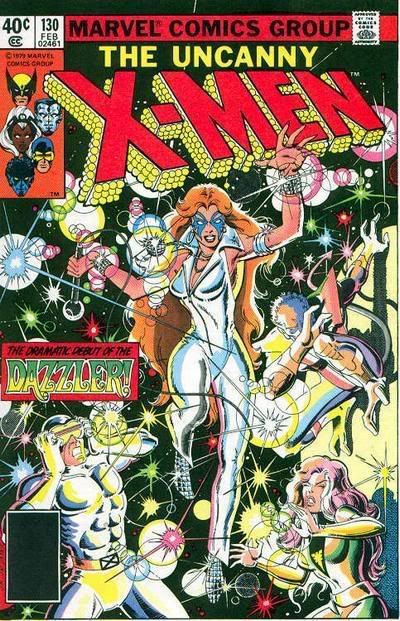

And regardless of all these things, the X-Men will still always go down in history as the gayest comic of all time simply for being the comic to introduce Dazzler to the world. Let’s face it, there may not be anything gayer than Dazzler.