10 Double Features for the 10 Best Picture Nominees

At 5:35 am (PST), the nominations for this year’s Academy Awards were announced. As has been my habit for the past several years, I have arisen at that early hour to see the announcements made. My own personal top-10 lists have never matched what has been nominated (my personal list can be read on my ‘blog here: http://witneyman.wordpress.com/2011/01/21/the-best-films-of-2010/), but I still watch the Awards like a dorky hawk, imbibing the Super Bowl atmosphere of it all, and loving every show-biz-shallow moment. As an extra achievement I can brag about, I had actually seen all 10 of the Best Picture nominees before the announcement, which was the first time I had seen them all since, I think, 1997.

But for those of us who have been so inundated with film advertising and annoying critical “buzz” sticking to our skin, that we risk losing sight of a film’s quality due to overexposure, I offer the list below. I have paired each of the Best Picture nominees with a quality “B” feature, which should serve as a tonal or technical brother. Perhaps with a spiritual pair, each of the nominees can stand in relief, and become better in comparison. Or, if not, perhaps this list will serve as an important list of recommendations; if you liked the “A” feature, check out my “B” selection.

“A” Feature: “Black Swan”

“B” Feature: “Videodrome”

Darren Aronofsky’s film was about a skittish and wispy ballerina who, through professional paranoia, virgin/whore hysterics, begins to slowly unravel. She abuses her body with bulimia, scratching, hangnail abuse, and, as the film progresses, bodily mutation. By the film’s end, we are unsure as to how much of what our heroine has witnessed is true, and how much is hallucination. When though about, certain characters may not even really exist.

In my mind, the only filmmaker who can match (indeed, who can outdo) Aronofsky’s use of hallucinatory mindfudgery – paired with mutant bodily horror – is David Cronenberg. And the best film of Cronenberg’s to pair with “Black Swan” would have to be his 1983 classic “Videodrome,” which follows the adventures of Max (James Woods), as how his reality begins to dissolve after he discovers a pirated S&M TV channel. While “Videodrome” deals with technology, and “Black Swan” deals with art, it can be said that both deal with the mind’s susceptibility to suggestion. Not to mention, they both have themes of bodily mutation, and the good solid mental earwig of unreliable narrators experiencing increasingly creepy hallucinations.

“A” Feature: “The Fighter”

“B” Feature: “Punch-Drunk Love”

One of the more notable elements of David O. Russel’s “The Fighter” was the lead character’s family. Mickey Ward (Mark Wahlberg) is a hard-wroking fighter, but seems to have little clout or personality when set next to his incredibly noisy gaggle of Edith Massey-like sisters, and their mama hen mother (Melissa Leo). It’s only the love of a quiet outsider eccentric (Amy Adams) that can really free him from his familial non-entity status.

A film that follows a similar pattern is P.T. Anderson’s 2002 love story “Punch-Drunk Love,” which starred Adam Sandler as a similarly henpecked brother in a sea of noisy sisters. He was quiet and shy, and, like Mickey, would vanish in the outsized personalities of his brood. He was given to violent outbursts as a result. The only thing that freed Sandler was the affection of an equally oddball ladylove, played by Emily Watson, who seems to share his violent proclivities.

One is shaped like a sports movie, and the other a crime drama. One feels laidback and the other is decidedly peculiar, but they are both, very powerfully, about the overwhelming familial bonds one must overcome-cum-incorporate into their lives.

“A” Feature: “Inception”

“B” Feature: “Paprika”

Christopher Nolan made a very clever action thriller with “Inception,” which took place largely inside dreams, where reality was mutable, the mildest of intentions can be magnified by the unforgiving lens of the subconscious, and all the characters were suave, well-dressed superspy espionage types bent on a secret mission within an alternate universe. The film was smart, refreshingly complicated, and, even if a bit cold and confusing, infused with a huge amount of cool.

A few years previous, however, master animation director Satoshi Kon tackled similar material in his underrated dram thriller “Paprika.” It followed a put-upon cop, and her attempts to smooth out the turbulent subconsciousnesses around her by entering their dreams, posing as a kickass superheroine named Paprika. Again, the dream world was an endlessly fascinating place of surreal reality mutability, and true intentions (or even identity) can be subjected to the simplest whim. It also had a dream superhero, focused on a task, while fighting nightmare images.

It is said that cinema is the artform to most closely resemble dreams. Two dream-like films in a row should make that adamant. If you’re still not feeling it after those two, check out “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.”

“A” Feature: “The Kids Are All Right”

“B” Feature: “Patrik, Age 1.5”

Lisa Cholodenko’s film is about a lesbian couple (Annette Bening and Julianne Moore) who must cope with the sudden appearance of their two childrens’ sperm donor (Mark Ruffalo), and the social awkwardness that he introduces. Is he to be treated as an interloper? Is he to be welcomed? His lothario status also throws a monkey wrench into the proceedings…

This year saw a sweet, underrated Swedish film called “Patrik, Age 1.5” from director Ella Lemhagen. In it, a gay couple attempt to adopt a 1.5-year-old boy, but accidentally get a homophobic, chain-smoking 15-year-old. While “Patrik, Age 1.5” ends on a sentimental note, its largely about a gay couple trying to incorporate a new family member into an idyll that they had spent years building, and how that family member can be seen as an invader, even if he was invited.

Put the two films back-to-back, and perhaps you’ll see more than a pair of queer films. You’ll see two refreshing films about a real and palpable family dynamic.

“A” Feature: “The King’s Speech”

“B” Feature: “I, Claudius”

Tom Hooper’s “The king’s Speech” is about King George VI (Colin Firth), and the crippling stammer that prevented him from being taklen seriously by his royal family and his country. Eventually, under the employ of a failed Australian actor-turned-speech therapist (Geoffrey Rush), he learned not only to speak properly, but learned to open up to other people, and become a good friend.

It may be unfair to include a 13-hour British miniseries from 1976 as a “B-Feature,” but I am struck by the similarities between the two. They are both about royal figured, untrusted by their families, and seen as jokes, who must overcome a stammer to eventually win the hearts of their nation. While George VI found solace in friendship, and strength through eventual support, emperor Claudius I (Derek Jacobi) used his wits and smarts to overcome his infirmities and speech impediments, and remain a sane voice in the swirling vortex of his family’s madness (and when you’re following Caligula as emperor, you’d better have some good excuses).

Both the film and the miniseries had Derek Jacobi, too, and I’m fond of just about anything he does.

“A” Feature: “127 Hours”

“B” Feature: “Into the Wild”

In Danny Boyle’s “127 Hours,” Aron Ralston (James Franco), in a fit of misplaced independence, and a need to prove himself isolated from the world, would often trek out into the canyons of Utah to climb rocks, hike dangerous paths, and ride his bike on roads long since untraveled by men. In an accident, Aron found his arm pinned between a boulder and a cliff face. He was stuck there for 127 hours. I think, by this point, we all know what he had to do to free himself.

In Sean Penn’s 2007 masterpiece, Christopher McCandless (Emile Hirsch), in a fit of perhaps misplace independence, and certainly a need to prove himself isolated from the world, would trek out into the wolds of North America, by canoe, by foot, by the very occasional ride, and seek out the wonders of nature, untainted by man. In an accident, McCandless found himself stranded in an abandoned bus, unable to move for lack of food, and a case of poisoning.

Here are two intense and heartfelt films about souls desperate to be alone in the wilderness, and the difficult paths that life provides… and yet how satisfying it can be, despite the pitfalls of extreme self-inflicted violence and eventual starvation.

“A” Feature: “The Social Network”

“B” Feature: “We Live in Public”

David Fincher’s excellent “The Social Network” tells the story of Facebook.com through the wounded, nerdy personality of its founder, Mark Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg knew computers very well, but was not so good with people, which is ironic, given that he is the founder of the current leader of socializing technology. He alienated the few friends he had, being the kind of person who is laser-pointed at the task at hand, to the deference of any meaningful human connection, and ended up losing a few lawsuits.

Ondi Timoner’s 2009 documentary “We Live in Public,” follows the true story of Josh Harris, one of the earlier internet pioneers, who founded several Internet-only TV stations, long before such things were widespread, and even before technology had caught up with his ideas. His filming experiments eventually led to the We Live in Public projects, where he would put people in compounds and film them 24 hours a day. He also eventually lived with his girlfriend, entirely filmed online. Josh Harris was good with machines, but not with people. He was laser-pointed on the task at hand. He eventually lost his girlfriend and alienated his family.

There is a grand irony in most recent communication technology. It allows us to stay in touch,but it’s all predicated on being alone in a room with a computer, assuring we never have to actually contact other people. Here is a pair of films that explore that irony through two of the mediums most notable personalities.

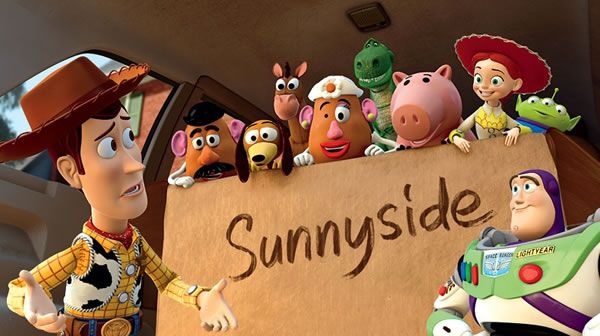

“A” Feature: “Toy Story 3”

“B” Feature: “After Life”

“Toy Story 3” is, despite its easy comedy and exciting action scenes, a film about death. This is a film about toys who must face their own mortality as their owner outgrows them, and where they will go from here. They dread The Dump, and look for alternates to oblivion. They think they find respite in the hands of a daycare center, but ultimately must face that they must be more content with making memories for children, than be concerned with their plight.

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 1998 film “After Life,” (which is one of the best films of the 1990s) is surprisingly similar. It takes place in the afterlife, where people gather in a calm, woodsy cabin to reminisce over their lives, and consult with employees of the Higher Power. They must select a single memory to take with them into oblivion, and the employees must reenact those memories on film. Both this cheery afterlife fantasy and the fantasy of talking toys are about the burden of happy memories, and how joy can overcome the inevitability of oblivion. I recommend both these films, and that they be seen back-to-back.

“A” Feature: “True Grit”

“B” Feature: “Lady Vengeance”

The Coen Bros’ “True Grit” is a surprisingly un-quirky, straightforward revenge tale, of a young girl and her dubiously skilled companions’ hunt to find the man who killed her father. She is a shrewd little girl, resourceful, and hellbent on revenge, despite her gentle demeanor and clearheadedness. This is a legitimate western, and a refreshing adventure.

At first glance, “True Grit” couldn’t be more different from Park Chan-wook’s 2005 horror film “Lady Vengeance,” but hear me out. Aside from being revenge tales, they both feature clever and resourceful young women who are wronged, and go about a horrifying task. They are both unprepared for wwhat they find, and they both exact the justice needed. While “Lady Vengeance” descends into a grand guingol orgy of lurid violence, and “True Grit” remains in the realm of adventure, they both have a similar structure, and both offer opposing points of view on the need for bloody revenge.

“A” Feature: “Winter’s Bone”

“B” Feature: “Undertow”

Debra Granik’s “Winter’s Bone” is about the fearsome backwoods unwritten justice standing in the way of a terrified-yet-stalwart young girl (Jennifer Lawrence) as she tries to uncover the more unsavory elements of her father’s past in order to salvage the family she is currently looking after. The world of the Ozarks is a harsh, muddy wilderness of closely-guarded secrets and misplaced codes of silence.

David Gordon Green’s 2004 film “Undertow” is about a teenage boy (Jamie Bell) traveling through the reed-encrusted backwoods of North Carolina, running from unwritten laws (and written ones) trying to protect his younger brother from the would-be sinister machinations of his unsavory kin (represented by Dermot Mulroney and Josh Lucas). The world of the wilderness is a morally absent wasteland of unwritten laws and frontier justice.

These are both quiet, poetic American Gothic films about escaping one’s unfortunate legacy, and trying to create one of one’s own, all in a wilderness of harsh rules, mistrust and outright hostility.

Witney Seibold is a professional film critic living in Los Angeles with his awesome wife, and his growing resentment of the younger generation. He writes film reviews on his ‘blog, Three Cheers for Darkened Years, which is, he feels, worth a look. It can be accessed here: http://witneyman.wordpress.com/ He also recently became the co-host of The B-Movies Podcast for Crave Online, and can be heard discussing movies with William Bibbiani on iTunes.